Figures of plebeian modernity

I had the fortune to shift into film studies in the mid-1990s as this relatively young discipline was hitting a crisis. As cinema reached its centenary the object of the discipline seemed to be dissolving. What is film in the digital age? What becomes of cinema in this 21st century when the way that we are watching films is changing so immensely?

This sense of crisis has motivated a looking back and a questioning of established methodological approaches to historicising cinema. Is film history really the history of the canonisation of a handful of films made in a few countries in Europe, the US and Japan? Is film history the history of the largely male filmmaker as the auteur? Is it the history of the heroic first discovery of this or that technology? Was the historical reality of the spectatorship of cinema ever the same as the conventionalised heuristic model of cinemagoing, of watching a film in a silent, darkened auditorium, as if the animated images on the screen were presented for your eyes only?

The gloss that the film historian Tom Gunning has put to this question of what it is to do film history properly is useful to bear in mind as I tell you about a particularly ephemeral and oral kind of cinema that had a lively, if not quite legitimate existence in Siam/Thailand from the 1930s to the mid 1980s. In the effort to shift the basis of writing cinema history away from overly text-based accounts, one that assumes that a given film, being made from reproducible technology, would represent the same things and tell the same story every time a reel of it is projected, Gunning proposes that the proper object of cinema history is the social nature of the interaction between a film and the contexts and spaces in which it meets particular audiences. The proper object of cinema history, he says, is “the place of the local in the history of a medium that aspires to the international, and indeed, the universal” [1].

Thinking about this issue is where doing cinema history overlaps with doing Thai studies, and let’s hope it has reverberations for Southeast Asia studies in a broader sense. How can an inquiry into the local characteristics of the film show – the event of film projection as performance – lead us to a greater understanding of the history of modernity in Siam. Cinema is, after all, an eminently modern thing. In what sense was cinema emblematic of modernity in 20th century Siam?

Where does one start looking for that proper object of cinema history?

This old photo tell us something about how standardised reels of celluloid became transformed once they reached Siam, in order to enhance their attractiveness as a type of film-voice performance. The Thai text at the bottom of the poster, in between the English and Chinese language titles of the film, says “อุดม ละม่อม พากย์ [udom lamom phaak].” Phaak is a fascinating verb whose etymology takes us to the masked dance performance khon, and it indicates a certain type of narration or voice performance. I’ve gone for a rather unusual term to render this term in English based on its appearance in the movie advert pages of the Bangkok Post newspaper in the 1950s, around the same time as the circulation of The Prisoner of Zenda in Siam. This film, shown some time in the early 1950s, at this particular cinema, was “versioned” by a performing duo called Udom and Lamom. This meant they performed a range of vocal utterances live, from somewhere inside the auditorium, as this sound film, The Prisoner of Zenda, was being projected. During this period, it became common for the names of the voice performers to be billed on the promotional poster, alongside the film title and the name of the film stars. The more famous the versionists, the bigger the text bearing their names on the posters displayed in front of the cinemas.

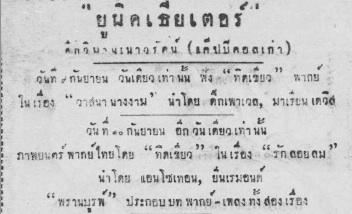

This Thai-language advert from an earlier period, 1938, gives a vivid sense of the otherness of the past in question. What’s being advertised is a film show, yet it was a show that wasn’t, strictly speaking, repeatable. Hence, “one day only.” Rather than inviting people to go watch a film, the advert told people to go “listen” to a man called Thid Khiew perform a film starring Dick Powell and Marion Davies.

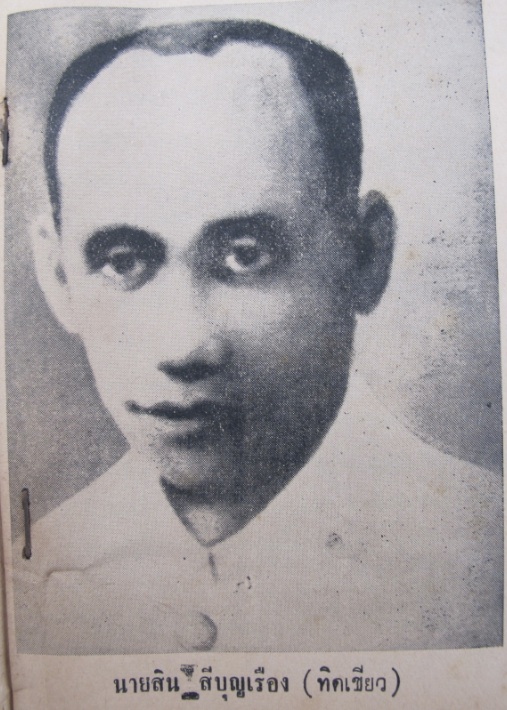

Here is Thid Khiew, the star versionist who, in the late 1930s, you were meant to go to the pictures to listen to. He’s now held up as the master-teacher of the art of the film-voice performance by the later generations of versionists. This is to give acknowledgement to the fact that he was the first to popularise versioning in Siam.

The emergence of versioning was intimately tied to the early twentieth century circulation of films from India. In the early 1930s, as the first sound films were make their way into the country, and as the first domestically made sound feature film was being unveiled in Bangkok cinemas, Thid Khiew, aka Sin Sibunruang, successfully experimented with adapting the narration convention of the masked dance to accompany an Indian mythological silent film, made by the Prabhat Films studio, based on an episode of the Ramayana. As the film was being projected he either stood or sat by the screen (details are hazy here), uttering a mix of rhyming poetic incantation, and rhyming dialogues, through a megaphone, accompanied by a musician.

So what was the cinema that Thid Khiew helped conjure into being with his successful adaptation of phaak khon [พากย์โขน], or masked dance narration, into phaak nang [พากย์หนัง], or film versioning?

The question is what follows when one shifts to thinking of cinema as a kind of live performance in Siam – a kind of entertainment subsumed within a pre-existing paradigm of theatricality, and a particularly oral kind of theatricality, one that places great value on the virtuosity of the speaker as performer – his or her capacity to rhyme, to improvise.

We can situate the cinema of versioning in Siam as a variant of what film theorists and historians have elsewhere called spoken cinema [2], which was neither silent nor sound cinema. Spoken cinema features voices that don’t speak in the film as such, voices that don’t come from the screen but aren’t unrelated to the screen either. The performing voices would often speak of the film to audiences in the here and now of the show. The attraction of the show would have been the voice performance as well as, or as much as, the stars on the screen, and perhaps even more so – the versionists’ power was that of the human presence that mediated the animated images on the screen whilst directly addressing you as this audience of this particular show.

Of course the coining of the term spoken cinema indicates that various types of it can be found in cinema histories elsewhere. Film narrators, lecturers or “barkers” were commonly active around the world in the first three or four decades of cinema. But what’s unusual about the Thai case is that the practice emerged at the end of the silent era. It gained momentum during the Second World War, and took off as a kind of parallel cinema to the more legitimate model of cinema – the good object of the subtitled sound film, or the Thai 35mm sound film with an international aspiration – becoming especially lively between the 1950s to the early 1970s.

Let’s fast forward to those decades and add the element of the 16mm filmmaking and projecting equipment. The accessibility of the lightweight, mobile 16mm projector and camera after the Second World War had a decisive impact in expanding the cinema of versioning. The mobile projector made it much easier for films and versionists to reach previously unreachable pockets of the country, such as remote villages, islands, districts, and small towns. From the 1950s a greater number of people could make a living being a versionist. There emerged the phenomenon of the regional star versionist, and significantly more women came into the profession.

This growth, which transformed versioned cinema into an unstable, never quite legitimate medium with its own codes and conventions, was partly an unintended consequence of the Second World War. When Siam was under Japanese occupation new film releases from allied countries couldn’t enter the country. Resourceful cinema exhibitors and theater owners adapted to the restricted flow of films by engaging versionists to give a fresh treatment, with each live performance, to the same old reels in their supply. Additionally, when the war ended there was a shortage of 35mm stock in Siam. As a result, creative local filmmakers experimented with shooting feature films on 16mm silent stock. With the commercial success of a 1949 film made in this manner the practice took off and lasted a little over twenty years.

This is the reason why local film historical periodisation calls the decades between the 1950s and early 1970s the “16mm era” [3]. There developed a mode of local, cheapie feature making characterised by shooting quickly on 16mm silent celluloid, and engaging one or more versionist to perform the voices and other foley or musical accompaniment at the point of the film’s projection. Film spectatorship during the 16mm era either took place within the confines of the darkened cinema auditorium, or in the open-air context of itinerant projection. Towards the end of the 16mm era the practice of live versioning was supplemented, in rather chaotic fashion, by playing a recorded tape reel of the performance during the projection of the celluloid reel (rather than shifting to the post-synch sound recording process). Foreign films shown during the 16mm period were still versioned, but practices did vary greatly here: first-class, first-run picture palaces in Bangkok, which largely showed Hollywood films, increasingly shifted to exclusively exhibiting films in their original soundtracks with subtitles from the 1960s. Itinerant, outdoor shows would project films on 16mm, Thai or otherwise, all of which would be versioned. Indian, Chinese and Japanese films shown in cinema theatres tended to be versioned.

What I now want to give a flavour of are three characteristic aspects of the cinema of versioning during the 16mm era that gesture toward the rise of a plebeian kind of modern culture in Siam during this same Cold War period. Firstly, versioned cinema was emblematic of plebeian modernity in the sense that it was made by a group of people, and especially women, who found a degree of economic stability through this art (or craft?), but who could not secure social status through this same profession. Many of the regional star versionists were high school dropouts, whether due to family poverty or their youthful delinquency. Yet, to use a clunky social theory term, they eventually became embourgeoisified through their ability to accumulate surplus income from versioning, in many cases leading to the ability to give their children a decent college education later on. Nevertheless, they themselves couldn’t rise socially because their art wasn’t respectable. Secondly, in the context of the versioning show on the itinerant circuit, it was a type of entertainment experienced by a rural population, and one that partly addressed them as consumers in an expanding market, thus incorporating them into the commercial sphere of cultural production and circulation. Thirdly, the unpredictability of live versioning, and the aesthetics and scale of the domestically made 16mm quickies, tended to elude the effort of the political leadership of the Cold War era to create a disciplined, standardised, modern Thai surface. That unpredictability, and the so-called amateurish aesthetics and cottage industry scale of the 16mm quickies, also fell far short of the desire of the cultural elite for the Westernised, standardised veneer, and the than samai [ทันสมัย, up to date] spectacle of national image and industry.

Who were the versionists of the 16mm/Cold War ear, and where were they situated socially? I’ll separate them according to gender. What’s significant about this third and forth generation versionist, or those who started apprenticing from the late 1950s or the late 1960s, compared to the second generation who came after Thid Khiew, is their mode of self-instruction. A lucky second generation versionist would have been one who managed to secure an apprentice with Thid Khiew, in the troupe founded by the master-teacher. The apprentice would have started out by running errands for the master and the elder members of the troupe in exchange for free boarding and face to face training with Thid Khiew.

Two talented history researchers, Chanchana Homsap and Nujaree Jaikeng, have been helping me interview the third and fourth generation versionists who used to work on the southern, northeastern and suburban Bangkok performance circuits. One phrase often came up when we asked them how they learned to perform the voices. They would often say “ครูพักลักจำ [khru phak lak jam],” which literally translates as “filching from the teacher as he’s resting.” In other words, they learnt the art of versioning through a self-concocted hotch-potch. An example is the account of a forth generation versionist in his late 50s, Khun Toe, who started his profession working on the Southern itinerant outdoor circuit and is now a successful owner of a film dubbing studio as well as the driving force behind many of the DVD and VCD releases of Thai films from the 16mm era. He gives a typical picture of being a movie mad teenager, obsessed with going to the movies in the town of Hat Yai and following two or three star versionists of the southern circuit in the 1960s and early 1970s. His intense cinephilia made him set his heart on becoming a versionist, and so he refused to go along with his mother’s wish for her son to go to university and get a respectable job like a sibling of his who’s now a judge, he says. Instead, Khun Toe went to the cinema and absorbed what the versionists did, mimicking and memorising the tricks they had up their sleeves. When he started out performing solo shows on the itinerant circuit he says he imitated the drawling, laconic style of the south’s star male versionist called Kannikar.

By the late 1950s, the troupe as a structure of artistic livelihood, a unit for organising and training budding voice performers, became diffused. Movie mad young men who went on to become third or forth generation versionists had no master-teacher to apprentice from as such. Instead, they learnt by going to the cinema or to itinerant film shows and mimicking the style and presence of the performers they were drawn to. They were cinephiles and fans who treated the film show as a kind of “manual,” to reference the historian Craig Reynolds’s conceptualisation of the basis of transmission of local epistemology in Siam [4]. Like the print technology that was Reynolds’s example of the modern life of manual knowledge, cinema – with its mix of partial reproducibility in this case, and its power of contagiousness, its tendency to urge anonymous spectators to mimic – could transmit knowledge while doing away with direct apprenticeship in the master’s house.

What about the women? The versioning partner of the southern star Kannikar was his wife Auntie Amara. When Thid Khiew and his rivals innovated the art of versioning in the 1930s, they were basically solo performers. This changed around a decade later, when women were engaged to accompany the male stars, performing the voices of women, children and, in some cases, creatures and animals. At least from the late 1950s, female performers began to be sent out on the itinerant circuit. What’s important to think about here is the ambiguity of their experience of physical and economic mobility. Through this artistic profession, some of the third and forth generation female versionists found themselves in a position of financial independence and ease from a young age, despite barely finishing high school. They travelled to adventurous, sometimes dangerous destinations, as the only woman in the troupe. As they became more experienced, a few of them secured a degree of authority as stars, or at least as named performers. Yet in most cases, even the stars remained subservient to the male stars within the troupe structure. And often the distinction between the professional and the private would collapse here, as many female versionists tended to be the wife of her male performing partner.

So let’s take as typical cases Auntie Amara and another female performer who kindly consented to being interviewed about her past on the condition of anonymity, and so we’ll call her Auntie B. Both are now in their early 70s. Both started working on the itinerant, open-air circuit in the late 1950s, when they were about 20, before gradually working their way up to the bigger cinemas in urban areas.

Auntie Amara spent her early childhood in Bangkok. After the Second World War her father left the lower ranks of the military and moved to Trang province in the south, where he found work as a cinema usher. She grew up following her father to the cinema and helping out her mother who had a food stall in the market nearby. In her self-description she was a bit of a tomboy who liked to sing loudly, and as is still evident in this photograph Auntie Amara was very good looking. When she was about 14 or 15 years old, a friend of her parents, an itinerant versionist, noticed that she had a good voice and asked if they would let her tour with him to towns and provinces in the far south. She would be the singer before the start of the versioning show and in between the reel changes. Her parents couldn’t afford to keep her in education and so let her go with him. Auntie Amara says she took the job because the money was very good; she could support her family with the earning from each trip. “I made as much as 30 baht a night as a singer, these days it would be like 300 baht.” After a while the uncle who took her along asked if she wanted to try versioning and she agreed, making 50 baht a night as a result.

So we have here the intertwined themes of family obligation and a woman’s patchy access to formal education. To remain in school would have been too much of a financial burden for Auntie Amara’s family, much less attractive as a route to mobility than an apprenticeship in this form of entertainment. Note also that Auntie Amara is someone who spent part of her childhood in Bangkok before moving to the south, in other words, to another language environment. Some readers would know from experience that one of the consequences of migration in early childhood is that the child becomes bi-lingual, tri-lingual, or multi-accented, someone who is generally good at code switching. This ability seems to be a key ingredient facilitating the popularity of the regional versionists, one of whose tricks for attracting the crowds was precisely their capacity to shift persuasively and amusingly into different accents and dialects.

Although there’s no space to go into detail here about the interplay between different vocalising styles and enunciating stances that any decent versionist had to learn to master, as a general rule of thumb a crucial attraction is the fluency with which a performer can shift across different registers of address and utterance. One ambiguity that has to be thought through in historicising the cinema of versioning in Siam concerns the accents and dialects with which regional versionists performed: firstly, why it was that they tended to perform in Central Thai rather than in the local languages or accents during the 16mm/Cold War era, and secondly, the contexts in which they felt it was appropriate to make the show more piquant by shifting into local languages, or at least by punctuating Central Thai speech with local slangs.

Unlike the movie mad teenage boys, Auntie B never dreamt of being a versionist, and indeed was initially very reluctant to take up the profession. Family obligation was the main compulsion in her case, but in a slightly different way to that of Auntie Amara’s. Auntie B was brought up by an aunt and uncle who had a film rental enterprise in the south. (This was a type of business that rented out films and voice performers to local cinemas, festivity hosts, and to any person or any group that wanted to hire a film-versioning show.) When she was in her late teens her guardians needed a female versionist for the enterprise, and so made her perform as part of their troupe.

In her colourful recollection, tears, fear of darkness, and melodramatic loss of sleep (and appetite!) marked the early years of her career as an itinerant performer. The troupe which consisted of Auntie B, a male versionist, a projectionist, a sound effects boy, and the cash master or troupe owner, would travel by rickety boats and bumpy jeeps to remote islands, or to those villages that had a wooden barn structure, a makeshift, multi-purpose entertainment hall with a stage that could be converted into a cinema auditorium upon the arrival of a travelling troupe. After the evening’s show, once the audience had left the hall to make their way home, the team would fold away the white cloth that functioned as the screen, and the electricity generator that had kept the projector and microphones going would be switched off. As the illumination from the light cone faded to nothing the hall and its surrounding area fell into shadowy, murky darkness, and amplified human voices gave way to whistling wind and the calling of invisible creatures. A barn emptied of the projector’s flickering light and the thronging bodies that jerked and hooted to the warm jokey grain of the voices present dramatically metamorphosed into an uncompromisingly hard, haunted sleeping quarter for the visiting entertainers. The men slept in a row on the flimsy wooden stage in front, says Auntie B, while she was left alone in the projection booth at the opposite end of the barn, cursing and petrified with fear of all that moved unseen in the dark. What kept her at the job, despite the tears and fear and loss of appetite? The money was good. “ I’d come back to Hat Yai from a ten-day trip in the with 500 baht in cash. A baht in weight of gold back then was 400 baht in price. I was barely 20 years old.”

Auntie B’s quiet reason for requesting to remain anonymous even to this day, so many decades after her retirement and indeed the dissipation of her artistic profession, is in itself haunting. She began to shift up from the itinerant circuit to performing in cinema theatres when she was spotted by a male star versionist who needed a female performing partner, but one who would agree to remain in the shadows. She was to be his เงาเสียง [ngao siang], or his “voice shadow.” She would do some of the voices but she wouldn’t be acknowledged as one half of the partnership as such. She wasn’t credited on the posters, and audiences were meant to believe that they’d come to experience a solo show by the male star. At the end of the show she was meant to wait until everyone had left the auditorium and the area in front of the cinema before sneaking down out of the projection room.

This theme of a woman’s subordination to the male versionist is echoed in other ways. One of the films that made Auntie B famous in her own right was a Hollywood musical with many female and child characters, all of whose voices she had to perform. Her male counterpart, a junior partner in terms of age and artistic experience, had so much less to do than her during this film, yet she received less payment than him. Did she complain? “No of course not, that was how it was. Back then, the man splits the money and the woman runs around making copies of the script if that needed doing, or buying the coffee and tea.”

Now let’s go back to the second point about how films reached spectators in the more remote parts of the country, via events that addressed them as consumers in an expanding market. A very typically Cold War dimension to this story is the role of road building and cars in facilitating the trips further afield of versioning troupes. There were four contexts in which film-performance shows were held in the outdoors: religious or carnivalesque festivities hosted by a local person or group; the show held by itinerant showmen who would wander to remote destinations during the less busy months in his annual calendar; the show to promote consumer goods product (see above photo); and lastly the anti-communist propaganda show of the film unit of the US Information Service.

The black and white photo above, which I happened to pick up from a vendor in Songkhla province, shows an important apparatus of the itinerant variety of spoken cinema during the 16mm period. There’s no accompanying information regarding the time or place of this particular show, but from the text at the side of the versioning car we can tell that it was tied to selling a brand of washing detergent. The 16mm projector would have been fitted inside the car, along with various types of sound equipment. The versionist would have performed sitting or standing by the car. The horn loudspeakers amplified the voices. The screen erected for the occasional would have been a temporary one, made there and then involving the labour of the versionist, the projectionist, and often the eager viewers hanging around waiting for the show to start. The frame of the screen was usually made of bamboo, cut and trimmed to size in the locality. The screen itself was a white sheet brought by the troupe.

A fourth generation versionist called Khun Tong, now in his late fifties, grew up in a small district around Yasothorn province in the northeast. In an interview with Chanchana Homsap, he remembers in vivid detail the film units that travelled to his hometown to put on a kind of commercial attractions show. The versionist would combine the film projection and voice performance with deliberately long breaks between the reel change, during which he would entice spectators to purchase a particular brand of small household goods, or food and medicinal items, that was sponsoring the film unit. Khun Tong could still reel off a long list of the brands that made their way to his hometown in the 1960s, “BL Hua [a brand of modern medicine], Flying Rabbit [a liquid herbal mixture for indigestion], Frog [batteries], Ovaltine, Halls [boiled sweets], Faeza [aka “Feather” shampoo], and Breeze [washing powder].” In a variation of the commercial practice of product placement in films, the versionist would crack jokes and tempt potential customers during the suspiciously leisurely 10-15 minutes reel change interval. Holding up a bottle he might say, “This is not a rocket it’s the Flying Rabbit… If you don’t have enough money now or you don’t feel like buying it tonight you don’t have to. We will be at the market tomorrow morning.”

The last point concerns the not quite legitimate status of versioning during the Cold War period. And this also implies the lack of cultural legitimacy of local 16mm quickies shot on silent film stock, which thereby necessitated and prolonged the practice of versioning until post-synch sound became the norm from the mid to late 1970s. This is a question that has to do with the relationship between practices of filmmaking and exhibition and those socially dominant discourses that shaped how cinema was thought about and experienced. Nang phaak was in this context framed as the bad, underdeveloped object within the dominant national-modernity discourse of development and discipline. The rhetorical investment in the orderly and in the disciplined surface also implied an eagerness to make technological standardisation hold. Film is a reproducible technology. The threat of film’s unruly circulation within the paradigm of live, improvisatory theatrical performance was the dissolution of the potential to harness reproducible technology’s promise of the standardisation of meaning and reception to the service of official nationalism. This was the reason why every now and then there erupted the threat, issued by representatives of the political regime or the censor board, of cleaning up the plebeian sphere of cinema by forcing versionists to perform on tape, which could then be submitted to the authorities in advance of a film’s release. Once their voices were recorded onto the tape track the nature of their performance could potentially be vetted, and the cut or ban ordered if necessary. Whether such threats were ever systematically pursued is another matter. In an inverse logic to that, Siam’s history of spoken cinema – with its strong and unusually enduring attraction of the live, the unpredictable, the ephemeral, and the disjunctive – must have been also a history of cinema’s potentiality as a wild, rebel zone. Must have been, might have been, could have been. Which verb it is that should be used to shape the historian’s characterisation of phaak nang in its time is the theoretical problematic and the political stake in returning to nang phaak now.

1. Tom Gunning, ‘The Scene of Speaking: Two Decades of Discovering the Film Lecturer,’ Iris v. 27, 1997, pp. 67-79.

2. Alain Boillat, ‘The Voice as a Component Part of Audiovisual Dispositives,’ in Cinema Beyond Film: Media Epistemology in the Modern Era, François Albera and Maria Tortajada, eds. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2010.

3. Charnvit Kasetsiri and Wannee Samranwet. ‘Phapphayon thai kap karn sang chat: Leuad thaharn thai-Phra jao chang pheuak-Baan rai na rao [Thai Films and Nation Building: Blood of the Thai Military, the King of the White Elephant, Our Home and Fields].’ Warasan Thammasat v. 19, no. 2, 1993, pp. 89-112.

4. Craig Reynolds, ‘Manual Knowledge: Theory and Practice,’ in Contesting Thai and Southeast Asian Pasts. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2006.

Text based on the lecture given at the Brown Bag lecture series, Southeast Asia Program, Cornell University, 20 September 2012.

May Adadol Ingawanij

Pingback: Haunted houses and ghostly crowds « siam16mm